courtesy of Lydia Liebman Promotions

It has been quite some time since I have had an opportunity to write about a release from Mosaic Records. Consulting my archives, I realized that the last occasion (which may have been the only one), took place during my tenure with Examiner.com. Ironically, the one article that I wrote appeared at the beginning of January of 2015, almost exactly seven years ago.

Mosaic releases may best be described as comprehensive anthologies. When I first started to focus on jazz listening in the late Nineties, I usually received Mosaic catalogs in the mail packaged with catalogs of Blue Note Records releases. Indeed, Mosaic was co-founded by Michael Cuscuna, the leading discographer for Blue Note. However, Mosaic anthologies were not strictly limited to the Blue Note catalog.

Every Mosaic anthology supplemented its collection of CDs with a booklet providing extensive background material. This included not only a nuts-and-bolts summary of the recording sessions but also a rich account of the content, usually on a track-by-track basis. The music itself was usually reissues of past recordings, but these were frequently supplemented with tracks of alternate takes that had not been previously released.

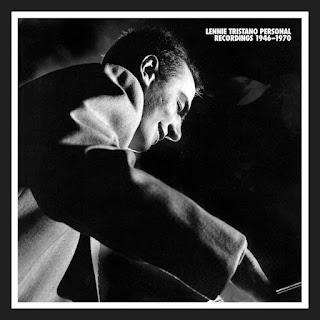

However, the latest Mosaic release consists entirely of tracks that have never been released. The title is Lennie Tristano Personal Recordings 1946–1970, and the hyperlink leads to the Mosaic Web page from which this collection may be ordered. The album was produced in partnership with Dot Time Records, the first time Mosaic has pursued such a joint endeavor. Dot Time was launched in 2012 and calls itself “The new light in jazz.” It is based in both New York and Bremen, Germany.

I am more than a little embarrassed to confess that I was entirely unaware of Tristano until I received a Mosaic anthology that was produced in 1997: The Complete Atlantic Recordings of Lennie Tristano, Lee Konitz & Warne Marsh. Listening to the six CDs in that collection was a major turning point and may even have served as the source for my referring to jazz as “chamber music by other means.” However, the operative word in this new release is “personal.” Tristano’s prodigious capacity for invention had as much to do with his own capacity for listening as with spontaneity in performance. Many of the tracks were recorded at his studio in Hollis or his house in Flushing, both neighborhoods in the New York City borough of Queens; and the recordings themselves captured not only solo work but also combo performances.

Given the dates in the title of the collection, however, one needs a generous amount of tolerance when it comes to the audio quality of the tracks. Indeed, seven of the tracks were captured on a wire recorder, a technology that was not replaced by tape until the Fifties. Fidelity was comparable to that of phonograph records in the Forties, but that is not saying much! Lenny Popkin, who wrote all of the track-by-track notes for the accompanying booklet, was also responsible for “Sound and Audio Restoration.” While the sound itself is noticeably dated, Popkin’s efforts make sure that one can hear all the notes that emerge from the complexity of the performances on all of the tracks of this collection.

Negotiating that complexity, on the other hand, is a matter of time. Given that the interaction between a record and the needle playing it would inevitably wear down the record itself, having a more “permanent” medium is definitely a virtue. In my own experience, I have to say that negotiating the complexities of Tristano’s capacities for invention emerges only gradually as one becomes more familiar with each of his tracks.

As might be expected, many (most?) of his compositions are contrafacts. In the course of my own listening, I have discovered that, more than I might have expected, there is often a motif (albeit a small one) that triggers awareness of the source behind the contrafact. For example, the track entitled “Call it Love” includes a clear motivic hint that “What Is This Thing Called Love?” is lurking in the infrastructure. On the other hand I have yet to figure out how (or why) “Don't Blame Me” serves as a background to “Cosmology” in the foreground! I suppose Tristano liked to keep his listeners guessing, but both he and his combo partners always seemed to know how to be playful about it.

Personally, I find that investing time in getting my head around a Tristano track is as rewarding as applying that time to compositions by Arnold Schoenberg or Anton Webern. Those encountering Tristano for the first time may benefit by beginning with the second CD in the collection, since this is the one consisting entirely of solo performances. There is a considerable amount of diversity across the eighteen tracks, sixteen of which are Tristano “originals” (with or without contrafacts); and the recordings themselves were made at three decidedly separated sessions in 1952, 1961, and 1970, respectively. Taken as a whole, the entire CD is not so much a journey as it is a series of rooms in a museum display; and contemporary technology allows the listener to amble among those rooms at his/her/their own pace in the process of sense-making.

No comments:

Post a Comment